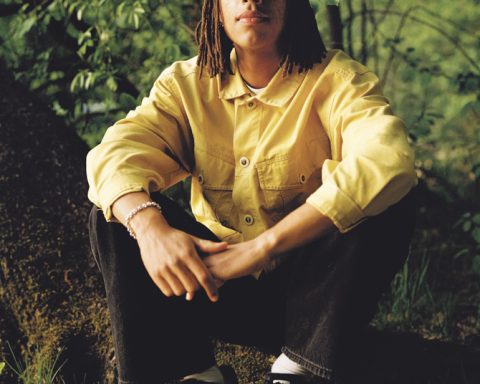

David March is a mental health nurse with over 20 years of experience in the field.

He is based in Whāingaroa and has recently launched Mental Health Pathfinder, offering personalised guidance for navigating the mental health system in Aotearoa. We met to talk about his experience, the barriers in the system, and his new venture.

What is your experience in mental health nursing?

I started working in a dementia care home before training as a mental health nurse in the UK. I’ve been in New Zealand for 20 years, working across acute inpatient care, drug and alcohol services, home-based treatment, assertive outreach, crisis teams, national crisis line triage, rural GP clinics, and HR in tertiary education. This diverse experience gives me a strong understanding of referral criteria, care provision, discharge thresholds, and the mental health system, which is invaluable in my current work.

What was it that led you into mental health nursing in the first place?

In my mid-teens, my parents bought a dementia care home, and we lived next door. Spending time with residents left a lasting impact. A visiting mental health nurse inspired me to pursue the profession, especially since training was government-funded at the time. It seemed a meaningful career with opportunities to work anywhere. Personal experiences also shaped my path. At 18, I lost a friend to suicide, triggering a period of deep depression that I didn’t seek help for due to limited resources and awareness. Friends and whānau faced mental health challenges, too. I wanted a career of service, to help others and make a difference.

What are some of the biggest lessons you’ve learned from working directly with people experiencing mental distress?

The most significant lesson is viewing health through a holistic lens, beyond the biopsychosocial model, to include the spiritual dimension. Textbooks teach biological, psychological, and social factors, but over time, I’ve recognised our interconnectedness—to each other, to place, to ancestors, and events. Understanding trauma, both subtle and overt, has been key learning along the way. Every person I’ve helped has deepened my insight into the nature of mental distress.

Has that holistic approach evolved over your career?

Early in my career, I worked on inpatient wards dominated by the medical model. My perspective shifted when I joined a community alcohol and drug service in Hamilton and pursued postgraduate study at the University of Otago. The Te Ariari o te Oranga framework taught me that a holistic understanding is essential for enhancing well-being in addiction and co-existing disorders. This approach often clashed with systems bypassing this crucial step.

I remember a kōrero with a kuia at the community house when I was working as a local mental health nurse here in town. She spoke about the importance of the spiritual dimension and how, for many Māori, this comes first and foremost in terms of understanding wellbeing within te ao Māori. I was inspired by Sir Mason Durie’s works while assisting in designing mental health policy at Wintec, working alongside a predominantly Māori pastoral care team to ensure the kaupapa for mental health support was not simply informed by the medical model.

Also, my partner, Anna, a somatic therapist trained by Gabor Maté, Peter Levine, Bessel van der Kolk, and Stephen Porges; her learning journey deepened my understanding of trauma. I work part-time on national crisis lines. I’ve noticed people often call reporting symptoms of depression and anxiety, but often they are also describing how the body is reacting to unresolved trauma. Over the years, I’ve learned to hone in on the underlying causes of the presenting symptoms. It’s like, if the canary in the coal mine stops chirping, removing the canary doesn’t address the issue. So the holistic assessment is a crucial step. As a nurse, it’s important to engage in continued education. I’m currently doing an advanced practice-nurse practitioner training, with a particular focus on supporting primary care (GPs), which continues to refine my holistic approach.

So, tell me about Mental Health Pathfinder.

Mental Health Pathfinder makes expert mental health guidance accessible without referral barriers, available promptly to individuals, whānau, and employers. On crisis lines, whānau often call about loved ones but struggle to access advice because services focus on the individual. We remove this barrier, offering mental health first aid and ongoing support without requiring personal details. We also support employers, drawing on my experience in corporate safety and well-being teams, where I saw gaps in occupational health. A major focus is assisting GP practices, particularly for people with mild to moderate needs who don’t qualify for specialist referrals or face long waitlists for community services. We’re connected through Healthlink for GP referrals, assessments, and guidance.

What are the biggest barriers people face when trying to access mental health support?

The biggest barrier is often reluctance or fear of reaching out. Many adopt a stoic mindset, thinking, “I got myself into this, I’ll get myself out.” I compare it to a car with warning lights flickering—people service vehicles, but ignore mental health signs. Early intervention could make the journey smoother, but many white-knuckle through distress. Other barriers include strict entry criteria for services, requiring assessments that many don’t meet. Whānau are often excluded, and cost or travel distances, especially for rural folks, are prohibitive. Mental Health Pathfinder is designed to remove these barriers with accessible, inclusive support.

What keeps you hopeful when you’re doing this work?

I love this work—it’s a privilege to have real conversations with people who place their trust in me. After nearly 25 years of practice, it feels like an art form, using my experience to guide someone through a crisis. People often say they’ve never spoken to a professional who “gets it”. While many skilled mental health professionals exist, some areas are really underserved. Helping someone in crisis and seeing their relief is a strong motivator to keep going.

Do you ever get overwhelmed by being stuck in a system that maybe doesn’t operate as well as it could?

I focus on what I can do. Instead of continually fighting to change a clunky system from within, I have focused on creating another option. Mental Health Pathfinder is a complementary service to bridge gaps and address barriers. It’s empowering to take initiative and create change. We’ve just launched, and the demand is clear. I’d love to see the service grow, bringing on more experienced mental health professionals.

What practical advice do you have for those experiencing mental distress?

Talk to your GP—they can point you to appropriate services in your area. Confidential support lines like 1737, Safe to Talk, or crisis lines are open to everyone and operate 24/7. Share your struggles with a trusted friend or whānau member; you don’t need to white-knuckle it alone. And, you know, we’re here too, Mental Health Pathfinder. We’re available and accessible; any GP can refer to us via Healthlink, or you can email us without needing a referral.

For expert guidance navigating Aotearoa’s mental health system, contact Mental Health Pathfinder at mentalhealthpathfinder.co.nz. We’re here for individuals, whānau, and employers.