Anzac Day will be particularly poignant for Raglan museum president Ken Soanes this year as he remembers a great uncle who died of war wounds on the other side of the world 100 years ago to the day.

Arthur William Watkins was one of 10 soldiers from Raglan to die in 1918, the last year of World War 1. All up, 29 of the 154 men from the district who served in the four-year war did not survive.

A sawmiller from Te Uku, Arthur was a stretcher-bearer on the front line, Ken told the Chronicle. After being wounded he was sent to England where he died on what is now Anzac Day, April 25.

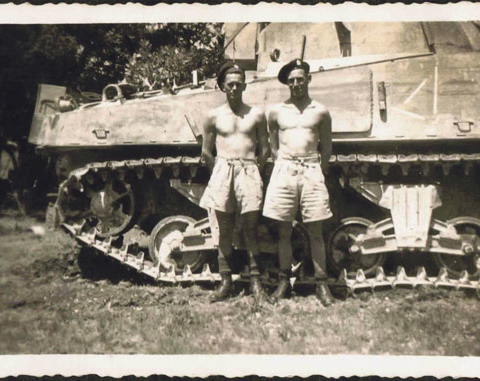

In Ken’s collection of photos sent home by his great-uncle while on active service in France and Belgium, there’s one with a message that reads: “Put this aside for me when I get back.”

It’s a very emotional family connection, Ken admits. “I really feel it on Anzac Day.”

There’s also a second link, as it has turned out.

Through his work on the museum’s ‘Raglan Remembers World War One’ exhibition, Ken has recently discovered he had a second great-uncle here, Malcolm Mackinnon, who also died in the war.

Research reveals he was the first teacher at Waitetuna School.

The permanent World War One exhibition includes not only a wall display and comprehensive touchscreen catalogue – with links to the Auckland Cenotaph – but also a ring-binder folder of local soldiers’ personal stories as supplied by their descendants.

“Every man has a story,” Ken observes as the Chronicle delves into a few of them.

Farmhand Kenneth Aubrey Moon was also one of the 10 who died in 1918 and whose name is inscribed, like those of his fallen Raglan district comrades, on the war memorial cenotaph downtown. He died on active service during the Ramleh War in Palestine.

Quite a few from Raglan went to Palestine where they fought in battles as fierce but lesser known than Gallipoli, says Ken.

Other 1918 victims of the war who have descendants still in the district include Patrick Pierce Phelan, who died in France and is related to the Shea family, and Francis Arthur Vercoe who died that year on his return from battle.

Benjamin Charles Vernon was another who died of his wounds in France in 1918, having been at a mounted rifles training camp five years earlier along with other Raglan soldiers.

Then there’s the story of Alfred Lawrence Galvan, who worked for his father Richard in the original blacksmiths in Cliff Street. Alfred also operated the launch ‘Harmony’ on Whaingaroa harbour, and his family tried to prevent him from going to war. But he was forced to enlist in 2017 only to die of pneumonia while in training in New Zealand the following year.

“There’s all sorts of stories … and court cases … about people getting caught in the ballot,” Ken reveals.

Four other locals are listed among 1918’s war casualties: Hugh Saunders Pain, Henry Lionel Coate, Gordon Dodderidge Ferriman and Henry William Phillips.

A 20-minute series of interviews with descendants of some of those from Raglan who fought in the war is also set up on computer on the museum’s mezzanine floor and makes for quite moving viewing, Ken says.

The series includes footage from longtime Raglan families who are still here today – like the Wallises, Sweetmans, Gibbisons and Pearts.

The wall display itself starts with a timeline showing where New Zealand and particularly Raglan soldiers were involved overseas.

It includes some interesting lesser known facts, Ken says, such as that the first Kiwi to serve in the war was from the Raglan district. He was Captain Herbert Ambrose Cooper, a Waitetuna farmer who joined the Royal Flying Corps in England.

Other sections of the exhibition reveal how a patriotic community back in Raglan raised in 1918 the equivalent of $70,000 for the NZ Red Cross through just one day’s fundraising in the local town hall, and how hundreds of horses were sent from Raglan to be used in the war effort.

Edith Symes