Tainui hapū advocate for the environment Angeline Greensill can explain the importance of a dune so simply that even kids can understand it.

“I tell them a dune is like a bank – you put money in the bank and when you need it you can draw from it.”

That’s what she told students from Wesley Primary School recently, when on a school camp at the Institute of Awesome in Raglan they took part in a Coastcare planting bee along Kākāriki Beach, west of Wainamu.

About 60 students have helped plant 2700 kōwhangatara/spinifex and pīngao native grasses, which trap windblown sand.

Raglan’s beaches and inner harbour experience considerable coastal erosion, which is particularly noticeable when it happens in areas that have been developed for reserves, infrastructure or property.

Angeline knows all about the erosion – her home is just metres away from being taken by the sea and is on the edge of a trial dune creation into which the students were planting.

“To me coastal erosion is a natural process that we have to work with,” says Angeline, who has seen the sand come and go over the years.

“You can tell when it’s time to give nature an extra hand. A couple of prominent rocks on the beach get covered with sand; then it is time.

“After the last storm, our pōhutukawa trees ended up on the beach so we decided to install some brush fascines to catch sand. My dad did the same thing successfully in 2003 when the surf club building that was here was removed by council after being threatened by erosion.

“We’re fortunate this time because Coastcare has helped with a sand push-up to create dune slopes rather than waiting for the sand traps to work.”

Coastcare Waikato coordinator Stacey Hills says the role of a dune system and sand-trapping plants can be difficult for people to get their head around.

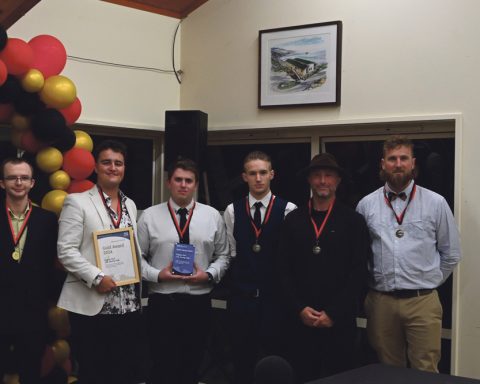

“Healthy dune systems naturally erode and build up in cycles over years,” says Stacey, who has led two other planting bees – back dune plantings with local students – in Raglan this year.

“They give protection to the land behind them by acting as a buffer against eroding wave action during storms or wild weather.

“The native dune grasses catch sand when the sea is nice and calm, and all that built up sand acts like buffer against the sea for when it’s not. The problem is the developed areas that are hard up against the coastline – they don’t have great widths of kōwhangatara and pīngao to allow for accretion/erosion cycles.”

Kākāriki Beach is an example of this. From the end car park on Riria Kereopa Memorial Drive towards the harbour there are no healthy dune systems, and the developed land has steep scarps and is covered in weeds.

For the 90-metre trial site, a bobcat and a digger were used to push up sand from below the high tide line to create a small dune against scarp.

“We’re trying to extend the strong dune system that exists to the west of this site,” says Stacey.

“If successful, in that the dune builds forward, then we will look to replicate that work in other areas along this stretch of beach.

“There are no guarantees when working with nature, unfortunately, as the natural rebuilding of a dune does require time – but hopefully this site gets time to recover before the next big storm.”

Restoration of the Whāingaroa coastline is a collaboration between Waikato Regional Council, Waikato District Council and Tainui hapū. Plantings are undertaken with keen members of the community, local schools, university students and occasionally corporate groups.